|

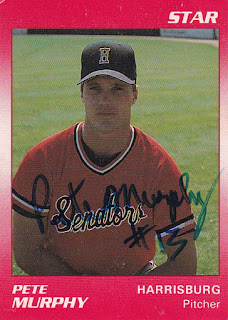

| Damaschke Field in Oneonta, NY, in 2009. Pete Murphy played for Oneonta rival Watertown in 1986 and 1987. (Photo by Greatest 21 Days) |

Part 2: After starring on both the St. Francis Prep baseball and football teams in high school, Murphy continued on in college, at Columbia University, where he could play both sports.

The future pro baseball player did both quarterback work and punted. His work as a punter remains among the school's best. He averaged more than 35 yards per punt through his career, good for 12th all-time at the school. He was also honorable mention all-Ivy his junior year.

But it was one outing in September 1985 that drew national media attention, the unwanted kind. It did so when Columbia's new coach, Jim Garrett used choice words to publicly blame a loss to Harvard, one where the team had been up 17-0 in the third quarter and then gave up 49 unanswered points, on Murphy, the punter.

"I want to see him when he graduates and goes to work downtown on Wall Street and does the things he did today," the coach told reporters of Murphy after the loss. "See how long he's gonna work for that company, how long Merrill Lynch or Smith Barney is going to have him around."

The incident not only became the talk of the campus, but also made national news.

Murphy recalled his brother calling from Brown. College football commentators, Brian Murphy relayed, were talking about it on CBS.

"That was kind of some unwanted publicity that I could have done without," Murphy said.

The coach apologized. But, for Murphy, then a senior, the damage had been done.

Murphy called it unfortunate. After that, he felt he couldn't play for him anymore.

"The biggest point that disappointed me was that I lost my senior year of football," Murphy said. "I felt that that was kind of taken away from me against my wishes."

Murphy instead focused on baseball.

He played fall ball for the first time.

As he got into the spring schedule, Murphy realized some scouts were around, but he hadn't really planned on getting drafted.

He had heard from some connections that the word had been put out on him, at least to take a look. But no scouts had actually approached him, Murphy recalled.

He learned later that his last start of the year for Columbia, against, of all schools, Harvard, sealed the deal for one Pittsburgh scout.

"The coach came out before the game, while I was warming up out in the bullpen, and said 'we really need this one,'" Murphy said. "So he kind of put a little extra pressure on me. I just felt good and I just kind of got in a groove and went right at guys."

He had a good fastball, a good slider and got a lot of three-pitch strikeouts and struck out 11 in all in a two-hit shutout.

"That was the thing the scout liked the most, he said he liked how aggressive I was and was able to go just right at guys," Murphy said.

But Murphy knew none of this.

He graduated and just started work at a law firm.

About three weeks in, came the draft and the call - from his brother Brian.

"We just got a call from the Pirates," Murphy remembered his brother relaying. "They just drafted you in the 23rd round."

"I was like, 'holy cow.' It was really cool," Murphy recalled. "I just turned around, hung up the phone, went into my boss and said, 'It's been nice, but got to go. Got to play baseball now."

Murphy recalled his boss completely understood.

Soon, Murphy was on his way to Florida.

Murphy Continued Down, Makes the Lobby

Murphy continued down in the second North Tower stairwell. It wasn't as crowded and he moved down quicker.

Throughout everything, Murphy recalled never hearing an announcement.

"Luckily, the lights never went off," Murphy said. "There was the smell of smoke and things like that."

Around maybe the 10th floor, he encountered water rushing in.

"There was like a cascade of water going down the stairs," Murphy recalled. "On every landing, there'd be maybe an inch of water and then like a cascade of water going down."

Just before that, the evacuees headed down started encountering firemen going up, firemen that Murphy knows likely did not survive.

The evacuees stayed to the right as the firemen passed.

"It was during that time that we heard from the firemen ... that we heard for the first time that it was a big plane," Murphy said. "And they were telling us, yeah, the other building just got hit also."

Up until that point, they had heard nothing about the second tower being hit, Murphy said.

"We couldn't hear anything because we were in the middle of the building. So we didn't feel it. We didn't hear it. So we were like, 'crap, this is really getting crazy.'"

Still, Murphy and the evacuees remained calm, he recalled.

Part of what allowed everyone to remain calm, Murphy believes, is that no one fathomed that the buildings would collapse.

"It would have been a totally different situation if people knew the clock was ticking," Murphy said, "that this building's not going to be here in an hour. It would have been chaos."

As Murphy made it to the ground floor, he recalled being momentarily disoriented.

His first thought: He had come out in some kind of back room area.

There was some smoke and dust. Lights were hanging down.

He had actually emerged in the North Tower's main lobby.

"It literally looked like a bomb went off in the lobby," Murphy said. "There was all this nice marble that you see down there, everything was just in bits on the floor."

Murphy's boss, the one Murphy had been planning on catching up with in the lobby for the meeting across the street, had been outside when the first plane hit. The boss later relayed to Murphy how he saw flames come out of the elevator shafts after impact, all the way down in the lobby, injuring people there.

Those were the same elevator shafts that Murphy had been about to enter just before the impact.

"I don't think I would have made it if I was in the elevator," Murphy said.

Murphy, however, had little time to think about the lobby. Police quickly ushered him and the other arriving evacuees further down, underground.

His Professional Baseball Career Begins

The newly drafted Murphy arrived in Bradenton, Fla., not sure what to expect, he recalled.

He'd heard a lot about places like the Pirates' spring training home but at the same time he didn't really know what it and the pros were really going to be like.

He arrived after morning workouts - and the place seemed empty.

But he did run into a fellow Pirates draftee, Pennsylvania-native Ed Hartman.

"He was the first guy that I met and he turned out to be one of my best buddies during my six years playing," Murphy said. "I guess my year, he was the only other college graduate, so we kind of had that in common."

Murphy also met the other players, heard their stories, where they were from, what they did.

"99.9 percent of the guys were all great guys, were all there for the same reasons, just trying to play, get better, get to the big leagues and have a good time," Murphy said.

Murphy stayed in Bradenton, playing in the Gulf Coast League, through July. He then moved up and spent the last month in short-season Watertown, NY.

The biggest difference between the two levels? The fans, Murphy said.

The rookie Gulf Coast League had no fans, by design. Watertown and the New York-Penn League did.

"When you introduced the fans, that's a whole different element," Murphy said. "They're out there, they're shouting for you, most of the time you're doing good and everything's fine. Then you'll have a bad night or something and you'll hear about it."

The challenge, he said, is to block all that out.

There were also the more mundane tasks, he recalled, like finding living arrangements.

"You don't get paid much, so that whole aspect of it also is budgeting and figuring out how to pay for things," Murphy said. "Some of it's tough, but it's all fun. It's living the dream and what can be better than getting paid to play baseball, even though it isn't much."

Murphy finished his first season with a 4-7 record over the two levels, with a 3.46 ERA. His work was good enough to break spring training with single-A Macon, Ga.

What he remembered about Macon was the heat.

"The whole pitching staff lost like 15 pounds in the first two months," Murphy recalled.

He then returned to Watertown for the second half of the season. Murphy went 9-3 there and helped Watertown to the playoffs, where the team fell in the finals.

Murphy recalled that year as fun, helped along by the team's manager, Jeff Cox.

But when he ran into some of those more mundane hardships of playing in the minor leagues, Murphy recalled his brother was there to keep things in perspective.

Having played football in college at Brown, Brian Murphy's sports career was over. But his brother Pete's was still going.

"He would have loved to have the chance to play pro football," Murphy said. "So he kind of kept it in perspective for me that if I started complaining or saying how hard it was, well my brother or 50,000 other guys would be more than happy to change spots with me in a second, so you've got to enjoy it while you have it."

See Part 3: Pete Murphy makes it home, comes full circle

No comments:

Post a Comment