|

| A memorial near Ground Zero in 2002. (Photo by Greatest 21 Days) |

Part 3: Guided away from the World Trade Center lobby down underground, Murphy recalled he and the other evacuees being sent through toward Trinity Church. They emerged behind it.

He didn't know it at the time, but he learned later that they didn't want the evacuees on the plaza as the jumpers had started.

"I wasn't aware of any of this stuff," Murphy said. "All I knew was there were big planes, it was probably a terrorist thing, that was it."

Once emerged from underground, he took a second to look up.

"That was the first time I saw," Murphy said. "I was like, holy cow, this is bad. This is not good."

He saw blood on the street near Trinity, where injured survivors had been.

"The whole time it was like 'I got to get out of here. I've got to get home. Everybody's going to be worried," Murphy said.

He had a wife at home, Mary. They'd wed three years earlier. They had two children, a 2-year-old and a 2-month-old.

Murphy made his way up to City Hall, just under a half a mile away.

The Trade Center continued to burn, but the towers remained standing.

His objectives: Try and get out of there and try to find a working phone.

On the far side of City Hall, Murphy tried the subways. They were still running. He got on and headed north, to Penn Station.

But Murphy, now about three miles north of the Trade Center, then starts to encounter roadblocks. He got on a train out, but service was cancelled as it prepared to leave, he recalled.

He also soon found subway service cancelled.

He did find a payphone that worked and called home. His wife wasn't there, but he left a message: He was alright.

"The problem is," Murphy said, "I didn't tell her where I was. I didn't tell her I was in Penn Station, just that 'I'm OK, I'll be alright.' And I just kind of took off."

He didn't tell her he was out of the building.

Soon, he learned later, his wife saw on the TV the phone calls played from people who had been in the towers and had likely still been in the towers when they collapsed.

"She didn't know where I was and on the TV she was watching the building fall down," Murphy said. "She thought I was dead."

His next successful call was maybe two hours later, he recalled. This time, he got his brother-in-law.

"Now for two hours, my wife and them didn't know where I was, didn't know if I was alive or if I was dead or anything," Murphy said, "so they were obviously very happy to hear from me."

From his brother-in-law, he also heard of a way out: The Midtown Tunnel.

AA and Time to Move On

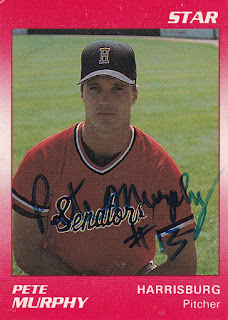

Murphy arrived at AA Harrisburg for the first time in 1989. He'd played his third year, in 1988, at single-A Salem. But the jump to AA marked a big step for the right-hander, just two steps away from the majors.

It also marked a big change.

"It becomes a lot more of an intellectual game, a mental game, where the pitchers and the batters are kind of working on strategies," Murphy said.

Murphy actually found it easier as the fielders behind him, like future major leaguers Moises Alou and Wes Chamberlain, were that much better.

"It was definitely a different experience pitching at that level," Murphy said.

In his second year there, in 1990, he briefly got sent back down to Salem as a new signing left him the odd man out at Harrisburg.

After a year and a half at AA, Murphy couldn't believe he was back at single-A.

"All the same people were still there, all the guys that came to the games that yelled at the players, they were saying the same stuff as two years prior," Murphy recalled. "It was really kind of funny and weird being there."

His stint there lasted three games. Soon, a guy got hurt and he moved back up and he recalled going on a run of scoreless innings.

Murphy turned in a 2.86 ERA that year at Harrisburg. That offseason, he earned a trip to Venezuela to play in the winter league there.

He pitched in front of thousands of people and to some big league players. He recalled pitching to a retired Tony Armas, who was a Venezuelan native, and Armas getting a veteran's ball call on a pitch Murphy described as right down the middle. The major league veteran didn't swing at it, so it couldn't have been a strike.

"The level of competition was so good, I felt I was able to turn my game up," Murphy said.

He also recalled helping his team to the playoffs and picking up a playoff win as a starter.

Back in the United States, he felt his numbers in 1989 and 1990 warranted a shot at AAA. But he didn't get called up.

Murphy returned to the minors in 1991, but again at AA. This time in Carolina. It ended up being his last year as a pro.

"The following season they wanted to send me back to AA again for another year and I'm like nah, I'm not doing that,'" Murphy said. "I did everything. I felt I proved myself, what do I got to do?"

Murphy had other options and he ultimately pursued them.

"I just kind of decided to concentrate on the next phase of my life and just move on," Murphy said.

By 1995, Murphy had begun work with Lehman Brothers.

Toward Home

As Murphy headed back down in a southerly direction to the Midtown Tunnel and the path off Manhattan that he hoped for, he saw smoke rising from the direction of the Trade Center.

He'd been far enough away from the collapse by the time it happened that he didn't experience it. In his continuing efforts to get off of Manhattan, Murphy said he hadn't heard what had happened.

He recalled being puzzled at the continuing smoke.

He made it to the tunnel and, with the assistance of police there, got into an SUV with other passengers to go through to Queens.

It was there, he said, that he learned for the first time that the towers had actually collapsed.

Murphy mentioned to the driver he'd been in the towers.

"The guy goes, 'yeah, man, I can't believe the buildings aren't there anymore,'" Murphy recalled. "I'm like, 'What? What are you talking about?'"

The driver confirmed that, yes, the buildings had collapsed.

Murphy couldn't believe it.

Murphy got out on the other side. He was now in Queens, not so far from where he spent is first years, in Woodside, making him familiar with the area.

His route on foot took him past the FDNY's main repair shop on Hunters Point Avenue. It had already become a staging area for equipment.

"Once I get past that, there's kind of a high spot, and I get to that high spot and that allows me to see all of Manhattan, especially downtown," Murphy said. "And I turn and that was the first time that I saw the buildings were gone."

"But my brain was playing tricks on me. I saw that the buildings weren't there. It was just the smoke. But my brain couldn't comprehend it," Murphy said. "It literally was putting the shadows of the buildings there because it was so used to seeing them and being in them."

The buildings were supposed to be there. But they weren't.

"I was like, 'holy cow,' so I just sat there for like five minutes just staring at it. ... It was just, it was just unbelievable."

He found another payphone and arranged for his wife and brother-in-law to pick him up. But there was still more walking to do to get to the pickup point.

He hit Queens Boulevard and merged into a large group of people who had also originated in Manhattan.

Murphy then found his wife and brother-in-law.

"We're not the most emotional people, but I think there were a lot of, there were hugs and things like that," Murphy said. "There was a lot of shock. There was a lot of shock going on. Mary kind of couldn't believe that I was alive."

The Years After

In the years after, Murphy's career went on. His family also expanded. He and his wife had two more children, for four total.

Of all those that died on 9/11, Murphy and Lehman Brothers only lost one coworker, believed to have been in a cafeteria higher up before the workday began.

Murphy also thinks about what all the firemen did and all the first responders did that day.

As for his family, his three oldest know his story, that he was there, he said. His youngest will later.

But in the years since, his life also came kind of full circle and back to baseball.

Murphy stayed on with Lehman Brothers into 2005 and, in 2019, he now works for the New York City Department of Education, heading up one of their technology divisions.

In between, in 2007, he found a consulting company that needed someone like him and he got the job.

That company did some sports work. That sports work ended up being with Major League Baseball.

Murphy started as a consultant. Then, after a couple months, he transferred over and became a full time employee - in the commissioner's office.

He managed internal programs, including the authentication system for game-used memorabilia. He went to multiple World Series, All-Star games.

He even got to see old friends he'd played with, who had gone on to more traditional baseball careers as coaches or in other roles.

But for Murphy, years after his own playing career stalled out short of the majors, he ended up making it anyway, just on a different path.

Further Reading:

- Research: Mike Weinburg played baseball, then became a New York City fireman. He died on 9/11

- Research: Mike Pomeranz played, then went into broadcasting. On 9/11, he was the morning anchor on CBS2 in New York and relayed news of the disaster as it unfolded

- Interview: Paul Abbott, then a pitcher for the Mariners, recalls the first game back after 9/11

Amazing story. I had two cards of this guy and didn't even realize he was in the WTC on 9/11. I was in midtown so was much more fortunate, but my experiences trying to get out of the city back to Long Island that day were very similar.

ReplyDeleteHi Bo, that was a crazy day and will never forget it.

ReplyDeleteWow, what a story! Peter was my boyfriend for awhile when he was with the Salem Buccaneers, but we lost touch after we broke up. Crazy to hear he was in the WTC on 9/11, but I’m so happy to hear he made it home safely.

ReplyDeleteHi Teri, thanks for the nice wishes. Yes it was a crazy day.

DeleteAmazing story, I actually grew up in Little Neck& played CYO baseball with Pete. He and his family were wonderful people. His mom& dad were@ all our games. I’m sure his father and Brian were with him on 9/11. So happy to see he has a wonderful family of his own.

ReplyDeleteHi Kevin, how have you been? Thanks for the nice words. I still remember those CYO days. My father and Brian were definitely with me on that day leading the way.

ReplyDelete